The Straight Facts on Felon in Possession Charges

What You Need to Know About Felon in Possession Charges

Felon in possession refers to the serious criminal offense of a person with a prior felony conviction unlawfully possessing a firearm or ammunition. If you’re facing this charge, here’s what you need to know immediately:

Quick Facts:

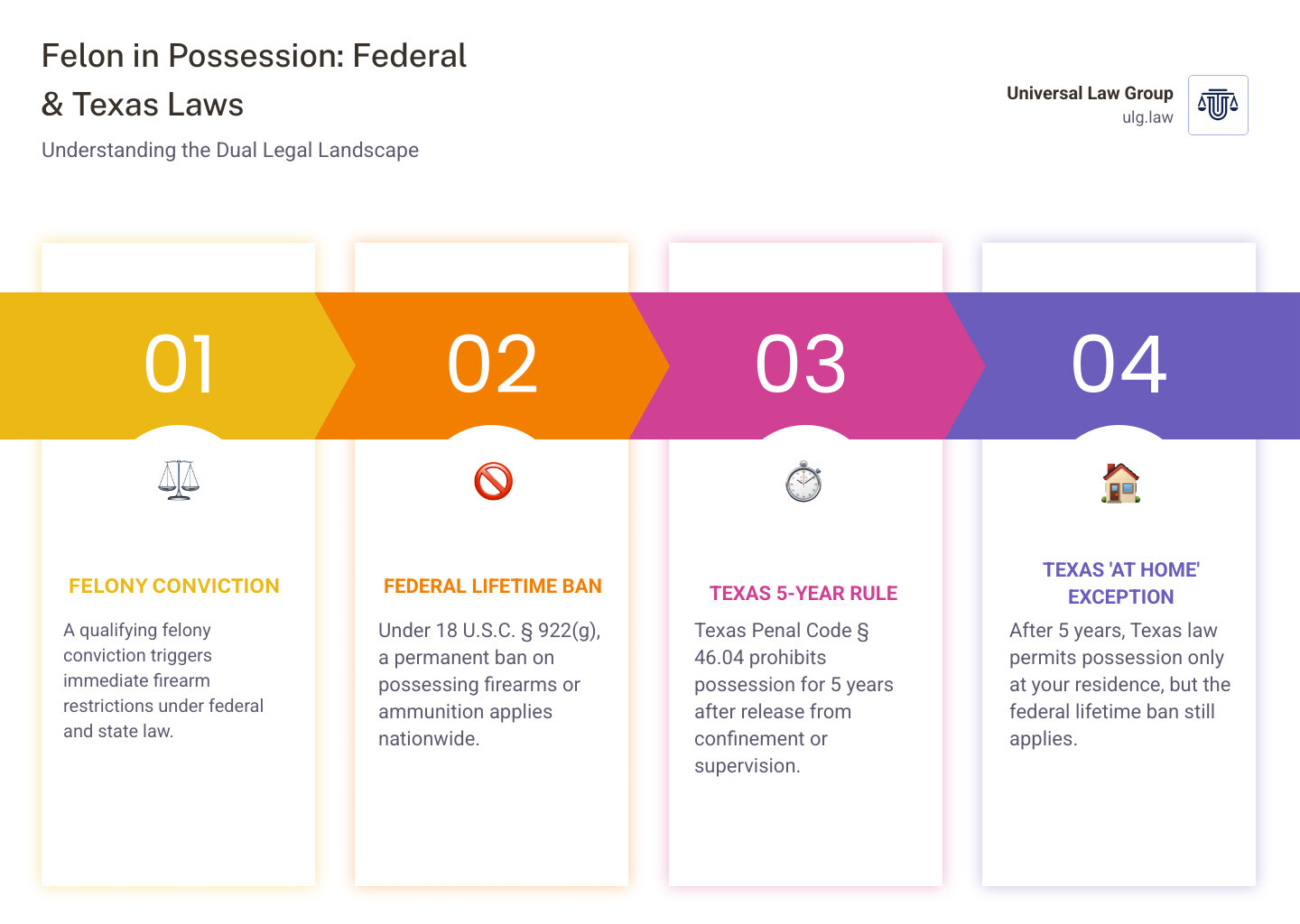

- Federal Law (18 U.S.C. § 922(g)): Imposes a lifetime ban on firearm possession for anyone convicted of a crime punishable by more than one year in prison

- Texas Law (Penal Code § 46.04): Prohibits possession for 5 years after release from confinement or supervision; after 5 years, possession is allowed only at your residence

- Federal Penalties: Up to 10 years in prison (or 15 years under the Armed Career Criminal Act), plus fines up to $250,000

- Texas Penalties: Third-degree felony carrying 2-10 years in prison and fines up to $10,000

- Key Issue: Federal and state laws conflict—what may be legal under Texas law after 5 years remains a federal crime

This is not a minor legal issue. In fiscal year 2024 alone, federal prosecutors secured 7,419 convictions under 18 U.S.C. § 922(g), with an average prison sentence of 71 months—nearly six years behind bars. For individuals with prior violent felonies or serious drug convictions sentenced under the Armed Career Criminal Act, that average jumps to a staggering 199 months, or over 16 years.

The consequences extend far beyond prison time. A conviction strips you of fundamental civil rights, impacts employment opportunities, and can permanently alter the trajectory of your life. The legal landscape is further complicated by the stark differences between federal and Texas state law, creating a minefield for anyone attempting to understand their rights and obligations.

Understanding “possession” is critical.

You don’t need to be caught holding a gun to face these charges. Federal courts recognize “constructive possession,” meaning you can be convicted if prosecutors prove you had the power and intent to exercise control over a firearm—even if it was in a shared vehicle, a roommate’s closet, or a storage unit. In one notable case, U.S. v. Davis, the Seventh Circuit upheld a conviction based on a firearm found in the defendant’s household, evidence of similar bags, and jail calls suggesting attempts to conceal the weapon.

The conflict between state and federal law creates unique challenges. Texas law permits felons to possess firearms at their residence after completing a five-year waiting period from release from confinement or supervision. This leads many to believe they’ve regained their Second Amendment rights. However, federal law recognizes no such exception—the ban is absolute and lifetime. This means a person who is legally possessing a firearm in their Houston home under Texas law is simultaneously committing a federal felony that could result in a decade in federal prison.

I’m Brian Nguyen, Managing Partner at Universal Law Group, and I lead our criminal defense division with experience prosecuting and defending complex felon in possession cases throughout Texas and federal courts. My background as a former Assistant District Attorney gives me unique insight into how prosecutors build these cases and the most effective defense strategies to protect your rights.

Understanding the Federal “Felon in Possession” Law

The federal government doesn’t mess around when it comes to convicted felons and firearms. The cornerstone of federal enforcement is 18 U.S.C. § 922(g), a provision within the Gun Control Act of 1968 that casts a wide net over who can and cannot possess firearms in this country.

This federal statute is straightforward in its reach: if you’ve been convicted of a crime punishable by more than one year in prison, you’re prohibited from shipping, transporting, possessing, or receiving any firearm or ammunition. Period. It doesn’t matter if you served your time, paid your debt to society, or turned your life around. Under federal law, that conviction creates a lifetime ban on firearm possession that follows you wherever you go in the United States.

This permanent prohibition is perhaps the most significant difference between federal law and Texas state law. While Texas offers a path—albeit a limited one—for felons to possess firearms at home after five years, federal law recognizes no such exception. The ban is absolute, and it applies nationwide. You can read the full text of the federal statute at The Cornell Law US Code Title 18.

Understanding how federal prosecutors prove a felon in possession charge is critical if you’re facing these allegations. It’s not just about being caught red-handed with a gun. The legal framework is more nuanced, and knowing what the government must prove can make all the difference in your defense.

The Three Elements of a Federal Charge

To convict you of being a felon in possession under federal law, prosecutors must prove three specific elements beyond a reasonable doubt. Think of these as three boxes they must check—miss even one, and the case should fail.

1. Proof of Knowledge

First, the government must prove you knowingly possessed a firearm or ammunition. The word “knowingly” is important here. Prosecutors must show you were aware of the firearm’s presence. You can’t accidentally possess something you didn’t know existed. However, as we’ll explore in the next section, “possession” doesn’t always mean what you might think it means.

2. Prior Conviction

Second, they must establish you had a prior felony conviction. Specifically, this means a conviction for any crime punishable by imprisonment for more than one year. Notice that it’s about the potential punishment, not what you actually served. Even if you received probation, if the crime could have resulted in more than a year behind bars, it counts as a qualifying felony under federal law.

3. Travel or Impact

Third, prosecutors must prove the firearm traveled in or affected interstate commerce. This element establishes federal jurisdiction—it’s what gives the federal government the authority to prosecute you rather than leaving it solely to state authorities. In practice, this is almost always the easiest element for prosecutors to prove. Nearly every firearm manufactured in modern times has crossed state lines at some point, whether during manufacturing, distribution, or sale. The burden of proof here is minimal.

The case U.S. v. Davis, 896 F.3d 784 (7th Cir. 2018) demonstrates how courts apply these elements in real-world situations. In Davis, the Seventh Circuit upheld a conviction even though the defendant never physically touched the firearm. The court found that circumstantial evidence—including the defendant’s status as head of household, the firearm being stored in a bag similar to one he owned, and recorded jail calls where he encouraged someone to lie about the weapon—was sufficient to prove knowing possession. This case underscores that federal prosecutors don’t need to catch you holding a gun to secure a conviction.

What is “Possession”? Actual vs. Constructive

When most people hear the word “possession,” they picture someone holding something in their hands or carrying it on their person. That’s certainly one type of possession, but federal law recognizes two distinct forms, and understanding both is essential.

Actual possession is the straightforward scenario. You have direct, immediate physical control over the firearm. It’s in your hand, in your pocket, or tucked into your waistband. There’s no question about whether you possess it—you’re in direct physical contact with the weapon.

Constructive possession is where things get complicated, and it’s also where many people facing felon in possession charges find themselves in legal jeopardy. Constructive possession means you didn’t have direct physical control over the firearm, but you knowingly had both the power and the intent to exercise dominion and control over it.

Real World Example

Let’s say you’re driving your car and get pulled over. Police find a handgun in the glove compartment. You weren’t touching it. You weren’t even aware it was there at that moment. Can you be charged with possession? Potentially, yes. If prosecutors can show you knew the gun was in the glove box and that you had access to it, they can argue constructive possession. The same principle applies to firearms found in your bedroom, your garage, or anywhere else you have regular access and control.

Shared spaces create particularly tricky situations. If you live with roommates or family members and a firearm is found in a common area, prosecutors may try to prove you had constructive possession based on your access to that space and any evidence suggesting you knew the weapon was there. The Davis case illustrates this perfectly—the firearm was found in a household where the defendant lived, and through various pieces of circumstantial evidence, the court determined he had constructive possession despite not physically holding the weapon.

This concept of constructive possession is why having a prior felony conviction requires extraordinary vigilance. You need to be acutely aware of what’s in your home, your vehicle, and any other space you regularly access. Even if a firearm belongs to someone else, if it’s in a location where you can access it and prosecutors can show you knew about it, you could face federal charges.

Defining “Firearm” and “Felony” Under Federal Law

The specific legal definitions of “firearm” and “felony” under federal law determine whether the felon in possession statute applies to your situation. These aren’t just dictionary definitions—they’re precise legal terms that can make or break a case.

What Does Firearm Mean?

Under 18 U.S.C. § 921, federal law defines a “firearm” expansively. It includes any weapon designed to or that may be readily converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive. This covers handguns, rifles, and shotguns, of course, but it also includes the frame or receiver of such weapons, firearm mufflers and silencers, and destructive devices. Even a starter pistol can qualify as a firearm under this definition if it’s designed to or can be converted to fire projectiles.

The broad definition means you can’t get creative with technicalities. A firearm doesn’t need to be in working condition to count—if it can be readily repaired or converted to fire, it qualifies. However, there is one notable exception: antique firearms manufactured before 1899 are generally excluded from the federal prohibition. This exception is narrow and specific, and it doesn’t apply to replicas of antique firearms that use conventional ammunition.

What Is the Definition of Felony?

The definition of “felony” for purposes of the federal ban is equally important. Federal law focuses on crimes punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year. This is about the maximum potential sentence the crime carries, not what you actually received. You might have gotten probation, served six months, or had your sentence suspended entirely—none of that matters. If the crime you were convicted of could have resulted in more than a year in prison, it’s a qualifying felony under 18 U.S.C. § 922(g).

There’s an important carve-out here: federal law specifically excludes certain state misdemeanors from triggering the ban. If your conviction was classified as a misdemeanor under state law and was punishable by two years or less, it generally won’t qualify as a disqualifying conviction under federal law. However, this exception is narrow, and many crimes that people think of as “minor” still carry potential sentences exceeding one year and therefore trigger the federal prohibition.

The interplay between what constitutes a firearm and what constitutes a disqualifying felony creates a complex web of federal regulations. What seems like a straightforward question—”Can I possess a gun?”—often requires careful legal analysis of your specific conviction, the type of weapon involved, and the circumstances of the alleged possession. This complexity is precisely why anyone facing a felon in possession charge needs experienced legal counsel who understands both the nuances of federal firearms law and how prosecutors build these cases.

While federal law takes a hard-line approach with its lifetime ban, Texas offers a different path—one that’s still restrictive, but acknowledges the possibility of limited firearm possession after a waiting period. This difference between state and federal law is where many people run into serious trouble, often believing they’re following the law when they’re actually at risk of federal prosecution.

The key statute you need to know is Texas Penal Code § 46.04, which spells out exactly when a person commits the offense of unlawful possession of a firearm in Texas. If you’re dealing with a prior felony conviction, understanding this law isn’t optional—it’s essential. You can read the complete text at Texas Penal Code – PENAL § 46.04. Unlawful Possession of Firearm on Westlaw.

The 5-Year Rule for a Felon in Possession in Texas

Here’s how Texas approaches felon in possession cases: if you’ve been convicted of a felony, you commit an offense by possessing a firearm during a specific time window. That window extends from the date of your conviction until the fifth anniversary of whichever comes later—your release from confinement or your release from supervision (whether that’s community supervision, parole, or mandatory supervision).

Let’s break that down with a real-world example. Say you were convicted of a felony in 2015, served three years in prison, and were released in 2018. You then spent two years on parole, completing that supervision in 2020. Under Texas law, your five-year waiting period doesn’t start when you left prison in 2018—it starts when you completed parole in 2020. That means you’d need to wait until 2025 before any firearm possession becomes legal under Texas law.

Getting this calculation right matters tremendously. We’ve seen cases where someone was off by just a few weeks in their calculations, leading to a felony charge that could have been avoided. The anniversary date isn’t approximate—it’s exact, and law enforcement will hold you to it.

The “At Home” Exception After Five Years

Once you’ve made it through that five-year waiting period, Texas law opens a narrow door. You can legally possess a firearm again, but there’s a significant catch: only at your residence.

This “at home” exception means exactly what it sounds like. After five years, you can have a firearm in your house, on your land, or in buildings directly connected to your property. You can keep one for home protection. You can have it in your bedroom closet or your gun safe. But the moment you step off your property with that firearm, you’re breaking Texas law.

You cannot carry it in your vehicle, even if it’s locked in the trunk; you cannot take it to a shooting range; you cannot bring it on a hunting trip, even on private land that isn’t yours; and you cannot store it at a friend’s house or in a storage unit off your property.

The restriction is absolute: possession at your residence only.

This is where many people make a critical mistake. They reach that five-year mark, assume they’ve regained their gun rights, and start carrying firearms or keeping them in their vehicles. Under Texas law alone, that’s illegal. But remember—and this cannot be stressed enough—federal law still applies. The federal lifetime ban doesn’t recognize any five-year waiting period or any home exception. What’s legal under Texas law after five years remains a serious federal felony that could send you to federal prison for a decade or more.

Other Texas-Specific Prohibitions

Texas law doesn’t stop at felony convictions when it comes to restricting firearm possession. The state has identified several other categories of people who pose potential risks and therefore face firearm restrictions.

If you’ve been convicted of a family violence misdemeanor under Section 22.01 (b)—specifically an assault involving family violence that’s punishable as a Class A misdemeanor—you face a similar five-year prohibition. The clock starts from the later of your release from confinement or completion of community supervision, just like with felonies.

Protective orders create another layer of prohibition. If you’re subject to certain types of protective orders (such as those issued under Chapter 85 of the Family Code or Article 17.292 of the Code of Criminal Procedure), you cannot possess a firearm after you’ve received notice of the order and before it expires. This applies regardless of whether you have any criminal convictions. The law recognizes that domestic situations can be volatile, and removing firearms from the equation can save lives.

Texas also prohibits members of criminal street gangs (as defined in Section 71.01 of the Penal Code) from carrying handguns on their person or in vehicles or watercraft. This applies if they intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly carry the weapon, reflecting the state’s effort to reduce gang-related violence.

These additional prohibitions show that Texas takes a comprehensive approach to firearm restrictions, looking beyond just felony convictions to address various public safety concerns. If you fall into any of these categories, it’s crucial to understand exactly what restrictions apply to you and for how long.

Federal vs. Texas Law: A Side-by-Side Comparison

The conflict between federal and Texas state law creates one of the most dangerous legal traps for individuals with felony convictions. Many people believe that once they’ve satisfied Texas requirements, they’ve regained their right to possess firearms. This assumption can lead to federal prosecution and years in prison—even when you’re following Texas law to the letter.

Understanding these differences isn’t just academic—it’s the difference between lawful possession under state law and committing a serious federal crime. Let me walk you through the key distinctions that every person with a prior conviction needs to understand.

Duration of the Ban

Duration of the Ban represents the most fundamental difference. Under federal law (18 U.S.C. § 922(g)), the prohibition on firearm possession is absolute and permanent. Once you have a qualifying felony conviction, federal law imposes a lifetime ban that never expires, regardless of how much time has passed or how you’ve turned your life around. There are no automatic restoration provisions.

Texas law takes a different approach. Under Penal Code § 46.04, the prohibition lasts for five years from the later of your release from confinement or completion of supervision (including probation or parole). This five-year period is strict—it starts from whichever date comes last. If you were released from prison in 2015 but remained on parole until 2018, your five-year countdown begins in 2018, not 2015.

Location of Possession

Location of Possession creates another critical distinction. Federal law prohibits possession everywhere—your home, your car, a friend’s house, a shooting range, anywhere within U.S. jurisdiction. There are no exceptions based on location.

Texas law, after the five-year waiting period, permits possession only at your residence. This means your dwelling and any land or buildings directly attached to it. You cannot legally carry the firearm in your vehicle, take it to a gun range, or have it at a hunting lease under Texas law. The moment you step off your property with that firearm, you’re violating state law—and you’re still violating federal law even while it sits in your home.

Types of Qualifying Convictions

Types of Qualifying Convictions also differ between jurisdictions. Federal law applies to any crime punishable by imprisonment for more than one year, with limited exceptions for certain state misdemeanors punishable by two years or less. This is based on the maximum possible sentence for the offense, not the actual sentence you received.

Texas law specifically addresses felony convictions, but also extends prohibitions to certain family violence misdemeanors under Section 22.01(b) and includes restrictions for individuals subject to protective orders. Texas also has specific provisions regarding criminal street gang members and their possession of handguns.

Restoration of Rights

Restoration of Rights presents perhaps the starkest contrast. Under federal law, your options for restoring firearm rights are extremely limited. You can pursue a presidential pardon, which is rare and difficult to obtain. There’s technically a provision for applying to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) for relief from disabilities, but Congress has not funded this program for decades, making it effectively unavailable.

Texas offers more realistic pathways. You can seek a gubernatorial pardon through the Board of Pardons and Paroles, though this still requires a complex legal process and is far from guaranteed. Some individuals may also explore judicial clemency options. If you’re interested in exploring these options, our Houston appellate lawyers have experience navigating these complex proceedings.

The Real-World Impact

The Real-World Impact of this conflict cannot be overstated. Imagine you completed your sentence in 2015, finished parole in 2017, and it’s now 2023. Under Texas law, you’re legally permitted to keep a firearm in your home for protection. You follow every Texas rule carefully—the gun never leaves your property. You believe you’re a law-abiding citizen.

Then federal agents execute a search warrant at your home for an unrelated matter. They find your legally possessed firearm under Texas law. Despite your compliance with state law, you’re now facing federal charges under 18 U.S.C. § 922(g) with potential penalties of up to 10 years in federal prison, or 15 years if you have prior qualifying convictions under the Armed Career Criminal Act.

This isn’t a hypothetical scenario—it happens regularly in Houston and throughout Texas. Federal prosecutors are not bound by state law, and they routinely charge individuals who are in technical compliance with Texas law but violating federal statutes. The federal government has its own priorities and enforcement strategies that don’t always align with state policy.

The Bottom Line

Federal law always supersedes state law when there’s a conflict. Just because Texas permits something after five years doesn’t mean the federal government recognizes that right. This is why anyone with a prior felony conviction must understand both sets of rules and realize that the more restrictive federal standard is the one that truly controls whether you can legally possess a firearm.

If you’re navigating this complex legal landscape, don’t rely on assumptions or informal advice. The stakes are too high, and the laws are too complicated for guesswork. At Universal Law Group, we help clients understand both state and federal firearm laws and develop strategies to protect their rights and their freedom. If you’re facing a felon in possession charge or have questions about your rights, contact our Houston criminal defense attorneys today for a consultation.